Gubernatorial impropriety

Anurag Tiwary & Anshumaan Mishra

Introduction

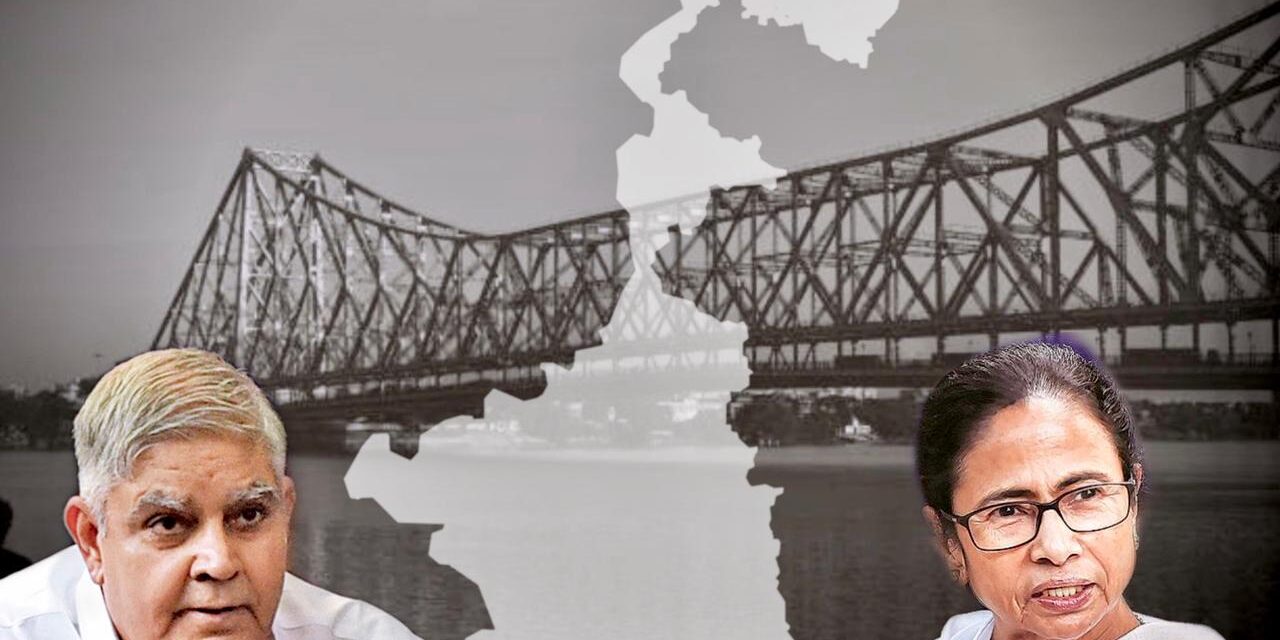

Jagdeep Dhankar, the Governor of West Bengal, has been out for quite some time to destabilize a newly elected government with a popular majority to the West Bengal Legislative Assembly, yet again! This time by making allegations of corruption against the Chief Minister and her government. Only recently he also made comments such as the anti-defection law being in full force in Bengal. In the past, he also visited areas hit by post-poll violence with local MPs from the BJP and made politically scathing remarks against the newly elected chief minister on issues such as the arrests of TMC ministers in the Narada Sting Operation Case. This, even though the veracity of these incidents is a matter of inquiry and is still under investigation.

In his excitement for some gubernatorial activism, the Senior Advocate and former politician turned Governor, Dhankar, has virtually refused to follow the “Manual of Protocols & Ceremonials of West Bengal Government” of which he is the constitutional head. This is not new -either of him or of governors in this country. Governor Dhankar, who, more often than not, finds pride in using Twitter to discharge his official duties, has done this repeatedly since the previous tenure of the Mamata Banerjee government.

But to be fair to the Hon’ble Governor of West Bengal, he is not to be blamed entirely for this. After all, this is a phenomenon that has gained customary status through its consistent use ever since independence and is increasingly common among governors in this country.

A Phenomenon?

It was only last year during the first wave of the pandemic when the Governor Shri of Maharashtra had mocked the Chief Minister publicly in a letter for being ‘secular’. Secularism is a basic structure of the constitution and of all the institutions in our democratic setup, the office of the governor as the constitutional head of the state is most expected to uphold the values enshrined in the text. However, that was far from reality in this case. The former governor of Rajasthan Shri Kalyan Singh in 2019 said, ‘as a party worker he would want the BJP to win. The Governor of Kerela Arif Mohammad Khan has had a similar history. In 2018, the Governor of Karnataka Vajubhai Vala did not allow the parties with a post-poll alliance having a majority to form the government and instead called a party with no simple majority and gave it two weeks to form the government. It was only after the Supreme Court intervened that the matter was resolved. Kiran Bedi in Puducherry, BS Koshiyari in Maharashtra, Satya Pal Malik in Jammu, and Kashmir and Tathagata Roy in Meghalaya are only a few recent examples when governors were engaged in a running feud with the state governments and wore their political ideologies on their sleeves.

It would be unfair to claim that this is a recent phenomenon. In fact, there are several instances in history when governors have engaged themselves in such acts of constitutional impropriety. Most notably but not limited to the SR Bommai case, the Rameshwar Prasad case, and the Nabam Rebia case. However, the scale and scope this time around are more than ever before.

It is only during the last half-decade that one has been witness to a new kind of politics at the level of the state governments, wherein, governors are equal participants in the political slugfest and are almost always racing to score a few brownie points. In the last five years, the rise of such new-age governors, who like to intervene in the day-to-day affairs of the state government, many times on Twitter and before the media, by making politically motivated statements in order to satisfy vested political interests, has increased. Jagdeep Dhankar, Kiran Bedi, and Anil Baijal are only a few examples.

The Threat

This raises an important question of constitutional and political significance. Is the office of the Governor, which is that of a constitutional head of the state who is expected to be impartial and non-arbitrary in his actions, slowly being converted into an extended official and political branch of the central government? The answer to this question for very obvious reasons lies in the affirmative.

However, little attention is paid to the unfortunate side-effect of such a phenomenon which is the gradual decline in the Centre-State relations in India thereby undermining our Constitutional goal of attaining Cooperative Federalism. Such a decline will also have major implications for national unity and will lead to an increase in ‘Regionalism’ and political violence. Both of which were evident during the West Bengal Assembly Elections held earlier this year.

It becomes important to understand that Federalism isn’t just a concept but also forms an integral part of the larger structural framework of this great nation and is one of the basic structures of our Constitution as held by the Honorable Supreme Court in the Keshavananda Bharati judgment and was later reiterated in the SR Bommai case.

Recommendations made by several committees

The ‘PV Rajamannar Committee’ in 1970, while recommending for the improvement of Centre-State relations, suggested that the Governor must be appointed with the approval of the state cabinet or by a high-powered body consisting of the Prime Minister and the Chief Minister. The ‘Sarkaria Commission’ also favored a similar idea. Later, in the ‘MM Punchi Report’ it was recommended that a person who is slated to be a governor should not have participated in active politics. It also suggested that the governor must not be removed at the whims and fancies of the central government, instead should be removed only at the behest of a resolution passed by the state legislature.

However, none of these recommendations were either accepted or even discussed on the floor of the Parliament house. This is evidently because irrespective of which political party is running the government at the Centre, each one of them intends to reduce the state government to the position of a department of the central government. This narrative was acceptable during the initial years post-independence because of concerns regarding national integrity, preventing disintegration, and secession. Centralization, initially, was indispensable and inevitable in a country that had 17 provinces and 565 independent princely states at the time of independence. However, with time, it is only believed that our democracy has strengthened, and such colonial traditions must be done away with.

Judicial Opinion

Even the Supreme Court in several of its judgments has held that a governor’s actions must be actuated by good faith and tempered by caution. In the landmark SR Bommai judgment, the apex court had held that “a governor must not be arbitrary and fanciful and that he must advance the cause of federalism and democracy in the contemporary constitutional landscape”. In 2012, the Supreme Court held in B.P. Singhal vs. Union of India that the “Governor is not an employee or an agent of the Union Government nor a part of any political team”.

The right model for appointment

One of the key commonalities among the existing propositions on the appointment of governors as recommended by several committees mentioned above is a ‘reduction in the power of the central government to appoint governors’ and simultaneously ‘ensuring an increased involvement of the state government’ in such appointments. The reason why this seems to be a fair model is that, in a democracy, it is the state government that has the moral right to rule. The moral argument underlying this issue stems from a democratic idea that after all, it is the state government that is elected by the people through a direct vote whereas the governor is nominated by the Centre and whose position is akin to that of a President who is supposed to act based on the advice of the Council of ministers headed by the Chief Minister.

Gautam Bhatia, while suggesting a radically different model argues that the office of the governor is a constitutional choke-point that was inserted only to maintain national unity if popular democracy was to ever unleash its own destruction and should therefore be done away with. He mentions that it is important for us, as a state, to reconsider whether such a constitutional choke-point serves any valid purpose today and whether it should continue to exist. It indeed is a strong idea that the Office of the governor is against both ‘popular democracy’ and ‘Federalism’ and should therefore be abolished.

A comparison between both the propositions above shows that while the former demands for the state governments to get a seat at the appointment table, the latter takes an extreme stance on the issue. On one hand, it does sound legitimate that doing away with such a choke-point is indeed important if the same national unity, for which this office was created in the first place, is to be maintained. However, it cannot be denied that the office of the governor is symbolic of an India whose states remain committed to the national dream and of constitutional machinery that is to act as an oversight body.

Conclusion

The recent developments in West Bengal have yet again brought the debate between elected vs. nominated out in the open and if at all we intend to prevent a full-blown constitutional crisis, and a slow erosion of our democratic traditions, we must put it to rest. This can only happen if, in deliberative democracy, the state governments are not made to feel left out from the process of appointment of the governors and are given a fair chance in choosing them.

Anurag is an ‘Impact Fellow’ at Global Governance Initiative. He is from the National Law University, Visakhapatnam. Anshumaan is from the National Law University, Odisha, and is a CAN Scholar. (The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author/s. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of The Policy Observer or our members.)

Related Articles

Privatization of Liquor: A Look Into the Loopholes of The Policy

The division of the city was done into 32 zones and licenses were based on the same. In June 2021, the tenders were issued for the application of L-7Z and L-7V licenses. The office of commission of the excise government of the national capital issued terms and conditions for the grant of licenses.

The Information Technology Rules, 2021- A Constitutional Scrutiny

A law prescribing the procedure for depriving a person of his ‘personal liberty has to meet the requirements of Article 19 and if not shall be struck down as arbitrary under Article 14. Liberties and restrictions should run parallel to each other. One overpowering the other would distort the fair working of the constitutional machinery.

Supreme Court: A populist institution?

Dr. Justice D.Y. Chandrachud while overruling ADM Jabalpur v Shivkant Shukla said that:

“When histories of nations are written and critiqued, there are judicial decisions at the forefront of liberty. Yet others have to be assigned to the archives, reflective of what was, but should never have been.”