How courts have failed rape victims, a series of events

Kumar Kartikeya

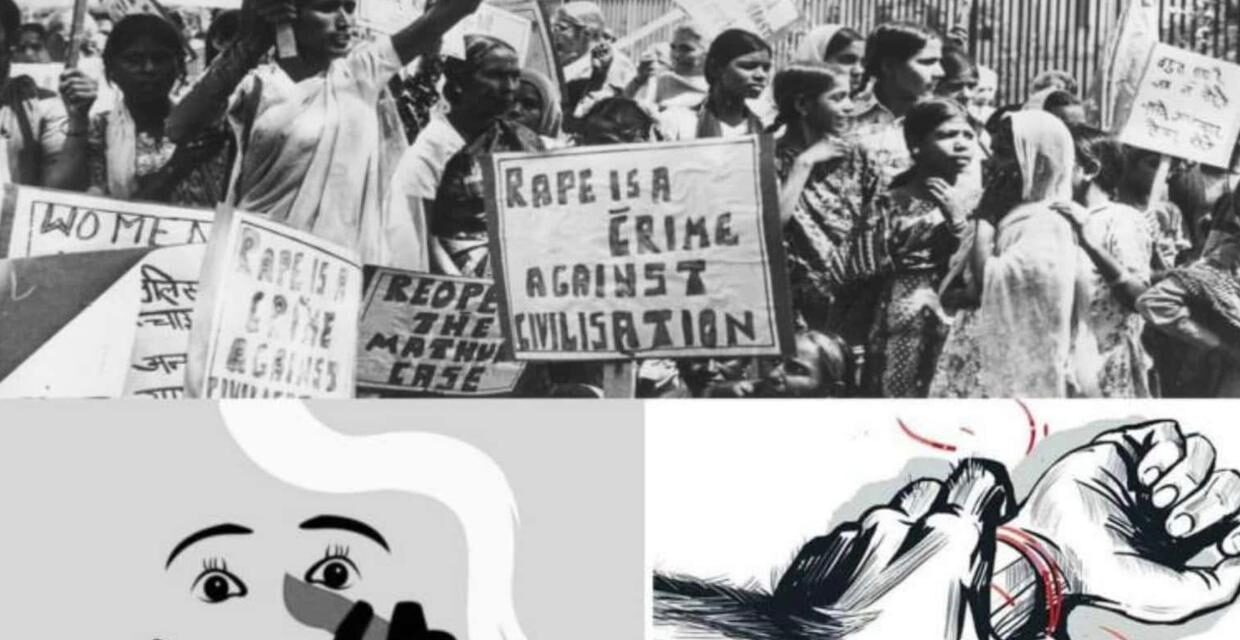

In the late 1970s and early 80s, the slogan that echoed in and around the Supreme court was “Mathura was raped twice, first by the police and then by the courts.” It was due to the Apex court’s acquittal of two policemen in the Mathura rape case. On the grounds that Mathura, who was only 14 or 16, was not of a “good character.” This slogan is very much relevant at this time.

On the 1st of March, 2021, a Supreme court bench headed by Former Chief justice S.A. Bobde was hearing a petition where a 23-year old government servant is accused of raping a minor girl when she was 16 years old. While hearing the case, the Chief justice asked the accused, “will you marry her?” Later the court also granted protection from arrest to the petitioner for four weeks.

Marrying your rapist is a traditional practice by Khap Panchayats and different panchayats in India. In 2015, a woman from Orissa married her rapist in jail, as the family considered that she had “no choice” other than to marry her rapist. The man was released on bail for the marriage ceremony later, the survivor’s family took back the lawsuit. In the same year, the High Court of Madras released a rapist from jail on parole so that he could ‘meditate‘ with his victim.

Similarly, in 2020, the High Court of Orissa issued bail to a man accused of raping a minor who was arrested, under the POCSO Act, for marrying his victim, now an adult. They were married in June when the perpetrator was out on interim 30-day parole. Robin Vadakkumchery, a convicted rapist, requested two-month parole from the High Court of Kerala to marry the girl he had raped and impregnated when she was only 16. This bail petition was rejected by the High court of Kerala.

In Madan Lal Vs. The State of M.P, the Supreme Court held that any reconciliation between the victim of a rape and the suspect would be a ‘spectacular sin’ in taking a gentle approach to rape cases and that there should be no compromise in such cases. The Apex court also strongly encouraged the Courts to remain apart from the marriage proposals offered by rapists.

The Hon’ble Chief justice’s statement in Mohit Subhash Chavan v State of Maharashtra came as a shocker when the court itself has warned and advised different courts to stay away from such proposals by convicted or alleged rapists.

Rightly as women’s rights activists claim that some legislations and legal precedents come from male-dominant societies. These patriarchal characteristics are often reflected in the order/judgment or statements rendered by some judges or lawmakers. The courts make those statements partly because of customary stereotypes that a woman, who is the victim of sexual harassment, should wedlock her rapist to defend her honor, particularly when the victim gets impregnated. Such thought derives from patriarchal conceptions that connect the human integrity of a woman to perceived notions of ‘celibacy’ and ‘sanctity.’ This oppressive ideology also triggers honor killings in India.

Rapists who are absolved of a crime and then married to a rape victim are normal practices that are still legal in many parts of the world. Turkey had legislation to marry-your-rapist which, was repealed in 2005. The Turkish Government planned to reintroduce a marriage-your-rapist bill to disqualify rapists by having themselves marry their victims was in the wake of the outcry of community feminists.

A very large number of women all around the world are deprived of the human right to their bodies, including the fundamental right to be free from sexual abuse. These crimes against women are the product of a global culture of sexism. The rampant culture of abuse has been under investigation for a while now. The acquittal of veteran journalist Priya Ramani in a defamation case filed by former minister MJ Akbar in relation to the MeToo movement was a new path for the feminist movement for equality in India: while this statement by the chief justice is a massive blow to society.

The courts must address the social stigma of victims within the lines of the statute, and only then can we genuinely bring about reformative change within the society: but, if the court itself operates on the grounds of cultural prejudice, reformation and development will stay static, and in the name of equality we would be heading deeper into a patriarchal tyranny. The least the courts can do for the safety of the victim is to keep the victim as far away from the accused as possible. If the courts succumb to societal stereotypes, then who should the victim look up to for justice?

Author Kumar Kartikeya is a student of law and co-founder of The Policy Observer. He tweets from @kumarkartikeyad.

(The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author/s. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of The Policy Observer or our members.)

Related Articles

The Republic of India

After independence, colonial India was divided into two parts- the newly found India and Pakistan. Punjab and Bengal were sliced down into two— amid violence, riots, rape, and assaults on women, resulting in countless deaths. However, this is just a portion of the story’s larger picture, not all of it.

Prevention of Terrorism Act: Encroaching Human Rights

The violent and arbitrary prosecutions by a thunderous majority against minuscule people in Sri Lanka is not a very recent phenomenon; rather it goes back to the Civil war fought from 1983 to 2009 between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Thousands of people were killed and continue to be prosecuted under PTA, in its aftermath.

Nepotism in the legal field: A tale of two young advocates

journey of a first generation lawyer. After having given three years of my life to the Bar, I ask myself ‘was it worth’! I am still looking for Answers.